Levelized Cost of Energy - Part 2

Inflation, Interest Rates, The CAPEX Cycle, and The Clean Energy Transition

Contents

Introduction

Are Interest Rates High Yet?

What’s Going On Now?

Looking Forward

The CAPEX Cycle

Concluding Remarks

Bitesize Edition

Last week, I explored how the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) was suppressed in renewables projects due to the low interest rate costs during the 2010s. The metric also contains aspects that are difficult to assume, such as maintenance and operating costs. I concluded that as an affordability metric of energy projects, it wasn’t the best.

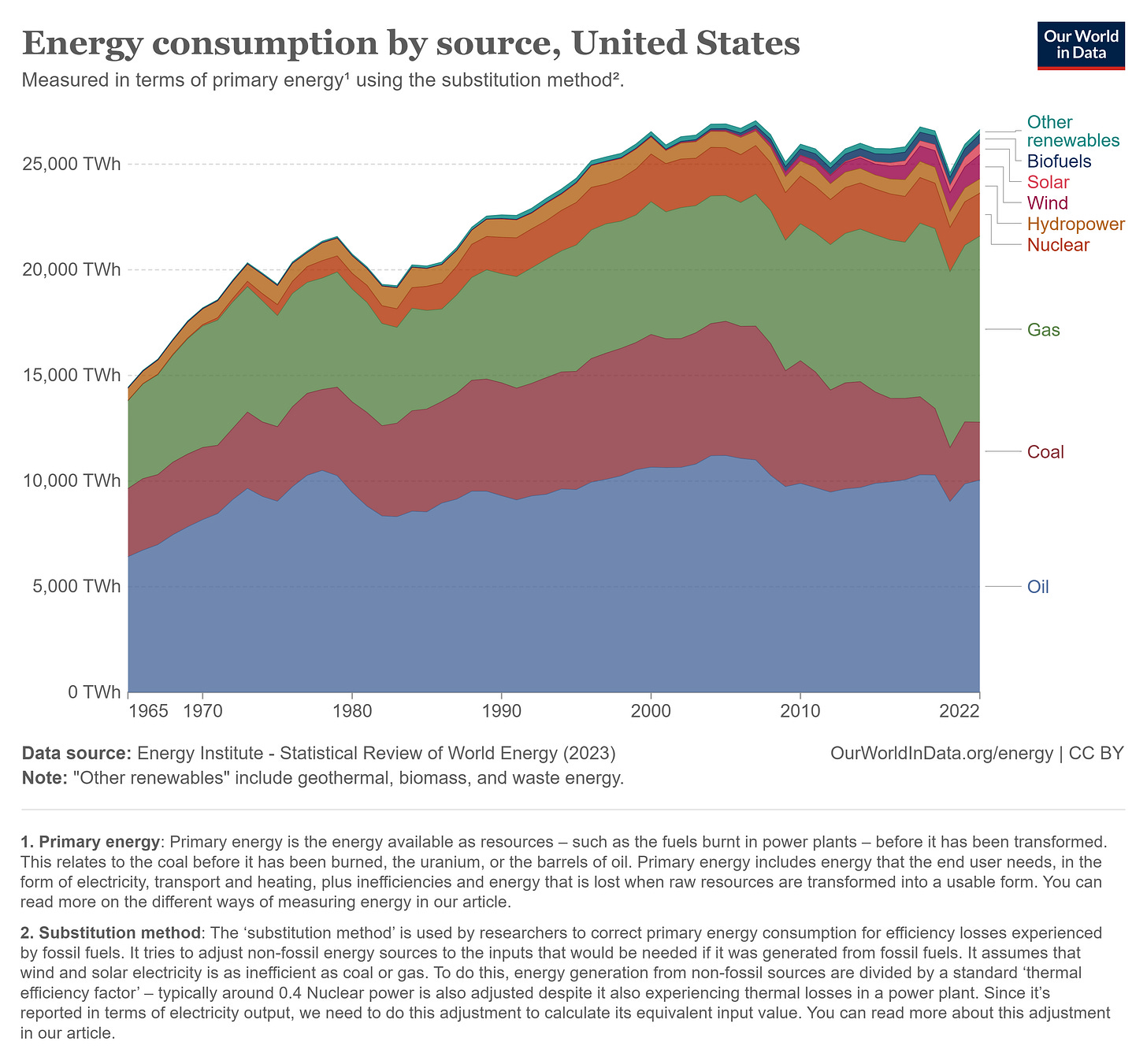

Today, I’m going to dive deeper into the financial side of the clean energy transition and how we need to pursue productive, profitable projects. I’ll explore the 1970s when we saw high spending for the war in Vietnam, which led to demand inflation. After this, we saw the OPEC embargo, which led to supply inflation. We’ve seen examples of supply inflation in the last few years with COVID-19 supply chain issues, and the war in Ukraine.

Today, as we stand low down on the mountain that is the clean energy transition, there is potential for supply-side inflation through scarce resources pivotal to the transition where demand is set to rise, such as copper and rare earth elements. But, there is also the potential for demand inflation, if the money supply is expanded too rapidly without productivity increasing along with it. Where does this leave us?

Introduction

When we look at the financial side of the clean energy transition, how can interest rates go anywhere but down?

A big claim, right? Especially when we’ve seen inflation rear its ugly head yet again in recent years and interest rates are often a tool used to lower demand for spending and bring inflation down.

Today, I’m going to hypothetically explore the clean energy transition through the scope of interest rates and inflation.

Interest Rates High Yet?

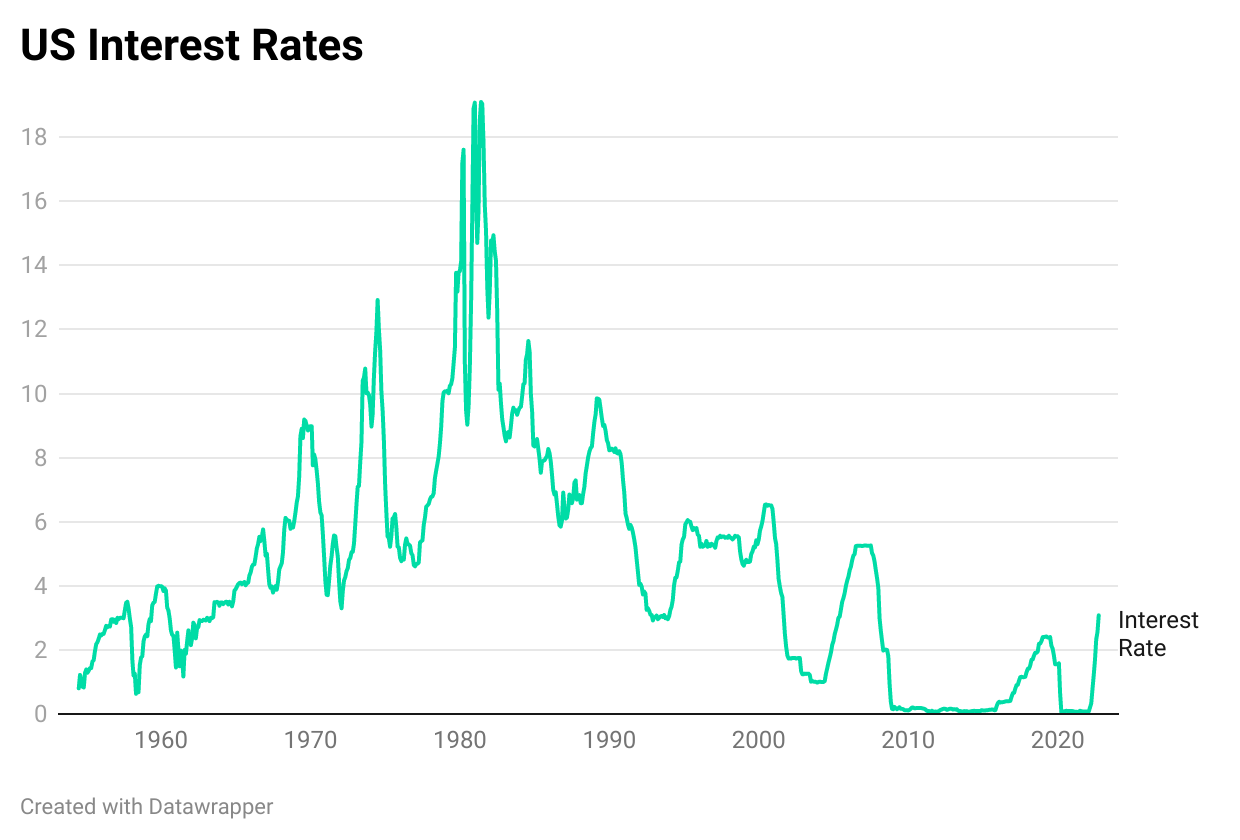

Historically, we’re not at high interest rates. Take a chart of interest rates over hundreds of years, or when Volcker ran the United States Federal Reserve and hiked rates to 20% in June 1981.

The previous period of inflation occurred in the 1970s in the United States. Many of us weren’t alive at the time to live through this period, and so we have to study it because even if it seems like this time is different, it very often isn’t. The same trends, behaviours, excesses, and undertones cause every crisis, even if the minutiae change each time.

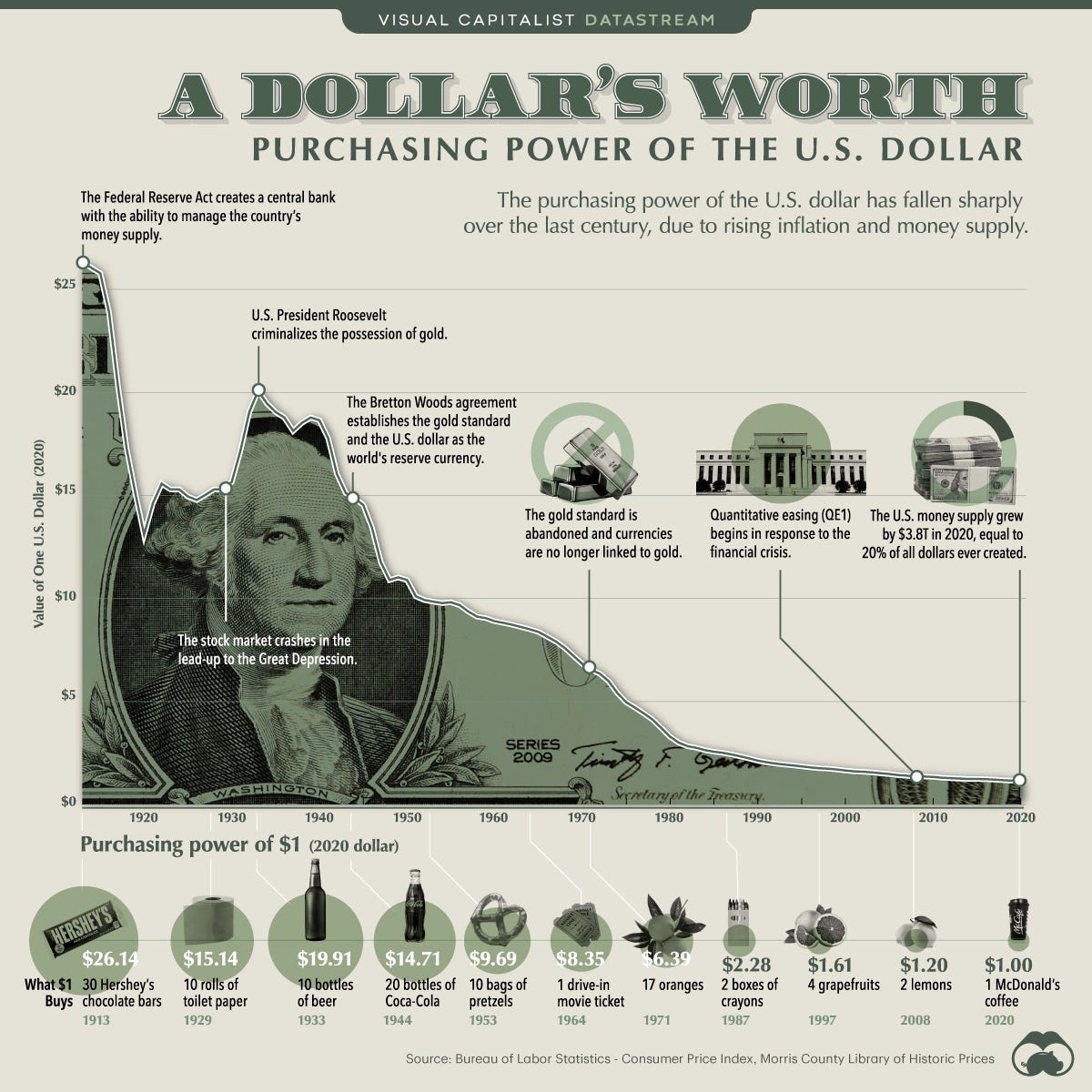

In the late 1960s, the United States was embroiled in a war in Vietnam. Wars cost money. This put pressure on deficits, which means the United States was spending more than it was earning in a specific period. Increased spending has inflationary pressures, and often has connections to politics. If a president has key policies that are going to cost money, they will spend spend spend if it makes their period in office a success.

In 1971, Richard Nixon ended the monetary system of the time, when gold could be traded for dollars. After World War Two, the Bretton Woods System saw many nations attach their exchange rates to the dollar. The dollar in turn could be exchanged for gold at a price of $35 per ounce. This saw dollars overvalued, and too many dollars floating around than gold to exchange them for.

Remember US inflation from the increased spending? Well, this was reducing the purchasing power of the dollar. You could buy less with the dollars you possessed as prices were rising, and so countries were demanding gold in return, known as an inflation hedge.

The United States couldn’t handle the demand for gold, and so Richard Nixon ended the monetary system of the time. The dollar was no longer exchangeable for gold.

We saw supply-side inflation enter the story when OPEC, the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Companies, issued an embargo on Western nations since they were supporting Israel in the Yom Kippur War of 1973, which I discussed here.

Energy prices skyrocketed, and a recession emerged. Fast forwarding a few years, Volcker inherited a situation where inflation was once again spiking in 1979 due to rising energy and food prices.

Small initial interest rate increases did little to slow rising prices. When you need access to necessities to live, it’s going to take a bigger demand hit to stop inflation in its tracks. The world ran on fossil fuels back then, and everybody needs food.

Interest rates were set at 13.7% in October 1979. By April 1980, it was 17.6%, and hit 20% in 1981.

Interest rates ensure debt costs are higher. This naturally reduces spending. This slows the economy and leads to recessions and job losses. Volcker left office in 1987, with inflation back at 3.4%, leaving two recessions and a peak of unemployment of 10.8% in 1982 in his wake. He has crushed inflation, but at what cost?