Contents

Introduction

Subsidies

Tariffs

Is More Better?

Concluding Remarks

Bitesize Edition

In the energy sector, subsidies are working to increase the speed at which projects are constructed. On the surface, this sounds great. But are subsidies all they are painted to be?

Subsidies for projects not making enough positive progress and innovation can lead to inefficiencies in production that are maintained much longer than typical market conditions would allow.

If we aren’t building energy projects suitable to our individual environments, and considering efficiency and affordability metrics, for example, we’re allowing for further inefficiencies to plague our energy transitions.

Then we see tariffs take a more prominent position on the global stage, and countries are seeking to limit the capabilities of other countries to undergo an energy transition. It’s not all rainbows when discussing subsidies, and it certainly isn’t with tariffs. Find out more below.

Introduction

Over the last month, I’ve been analysing different metrics we can use to assess the affordability of energy projects. In the pursuit of a cleaner energy world, many developed countries are putting huge financial efforts into transforming their energy sectors, many efforts through subsidies and occasionally, tariffs on other countries to boost domestic production. Do subsidies help more than they hurt? How are tariffs being utilized as a geopolitical weapon? Find out more below!

Subsidies

In 2022, global subsidies for fossil fuels breached $1T for the first time.

Subsidies are often seen as the fuel to get new energy projects off the ground. The encouragement of subsidies can spark further investment, contribute to lower costs, and aid in accelerating innovation. This paints a great picture. I usually embody the mindset of an optimist, but the pessimist within me asked a question: Money is being spent, and whenever money is spent, somebody is paying a cost. When it comes to subsidies, who pays the cost?

Funding for government budgets is often paid by taxpayers. Government deficits from high spending lead to cuts in other areas or greater borrowing. In the UK, where towns are witnessing buildings left derelict and bordered up, we are seeing a decline in public services, especially represented in the North-South divide.

However, if we are to transform our energy sector, subsidies are important. Opportunity cost must be considered. The funds used in energy projects could have been used elsewhere, but energy equals life. It’s likely the use of subsidies in energy projects is likely a good utilization of subsidies.

We do need to consider though if other financial instruments or methods of funding exist that could see more success. China’s centralized state-level model versus the market-driven economy of many Western countries is one such difference in societal structure we see in the world regarding government policy and spending. In the West, projects are supposed to be chosen based on market demand and profitability. So why have we recently seen projects such as Vogtle Units 3 and 4, and Hinkley Point C so heavily overscheduled and over budget? In comparison, China is building nuclear power plants in 5-10 years, and exploring innovative new technologies within the nuclear sector. Why is there such a gap in innovation and infrastructure project buildout in the West and China?

China uses centralised planning on long time frames that align with national goals. They have interests in multiple key innovative technology sectors, and their market share in many is growing, such as solar, electric vehicles, and now nuclear energy. Countries in the West realised this in 2015 when China released Made in 2025, and now they’re playing catch up. Projects in China are also less encumbered with bureaucratic red tape. The four-year political cycle when it comes to energy policy can see projects stop and start multiple times in the West. Not that I’m promoting political systems that see power aligned with one individual or one group, but we need some streamlined policy between leaders, and energy is a key area to pursue this cooperation, regardless of political beliefs.

We could discuss for hours as to whether subsidies are necessary. New technologies often need subsidies to get off the ground. Initial research and development can see multiple cycles of innovation occur before a design even reaches the physical testing stage. These new technologies are also competing with established energy sources such as fossil fuels, that have seen economies of scale and infrastructure buildout lower costs. What is clear is that this necessity is influenced by the maturity of the technology being subsidised, the energy market conditions, and the overall policy goal. Policy and regulation are two issues currently hindering the effectiveness of these subsidies.

What role do private companies play in innovation in the energy sector in market-driven economies in the West? Do the first players in innovative sectors become the winners? The new sectors are risky, with revenues initially being small for rather expensive research, development, construction, and the beginning of operation. To incite a level of investment needed, government subsidies would reduce the riskiness of the investment, and hence likely attract greater investment from private companies. With increased investment comes decreased risk and the incentive for more investment.

On the flip side, inefficiencies fuelled by subsidies remain inefficient and actually stifle innovation. We hence have to consider our environments, energy efficiency, and energy affordability as I’ve been discussing over the last few months.

As every country is working to reshape their energy sectors individually, one way in which some countries are enacting technological warfare with one another is through the use of tariffs.

Tariffs

A tariff is a tax imposed by one country on the goods and services imported from another. Importantly, it is the country importing who pays this tax. The aim is to make imports more expensive so domestic production is boosted and preferred. The exporting country will make less revenue if the importing country prefers domestic sources. According to the US Customs and Border Protection Department, after Trump’s tariffs in his first Presidency, the revenue of customs duties of $41.6B in fiscal year 2018 rose to $71.9B in fiscal year 2019.

The increase in revenue for a government isn’t the only effect of tariffs, and considering the balance of additional revenue versus additional costs ensures the tariffs provide greater benefits than drawbacks.

One key negative of tariffs is reduced competition. Industries of a monopolistic or duopolistic (two-company industry) nature possess mega-corporations that aren’t motivated by competition due to their sheer size and market share. Regulation can be influenced by and made to benefit these companies, and hence protect them, disadvantaging newer and more innovative companies.

This is opposite to what occurs in a sector of perfect competition. Perfect competition refers to the imaginary scenario where all firms have access to the same products and information. Thus companies must have the lowest price possible or their rivals will undercut them.

Of course, it’s more difficult to establish a company in an environment of perfect competition, and there can be multiple winners who advance the sector. Also, no sector has all the companies with the same products and information, so this is unrealistic. But within sectors with reduced competition such as monopolies, a company can charge any price it wishes. This is reinforced further when goods and services become more expensive internationally after tariffs.

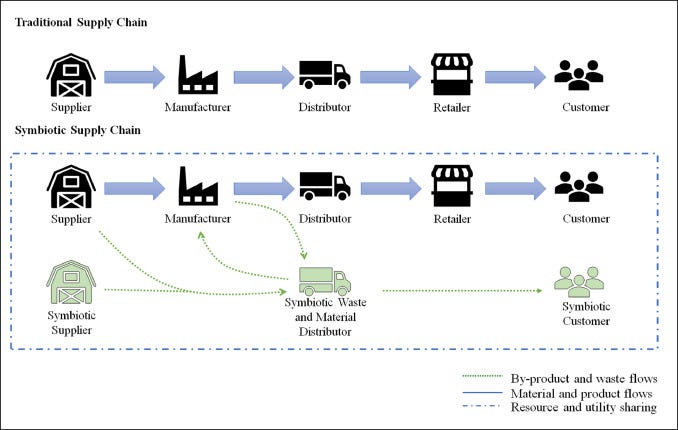

Consider the supply chain below:

A tariff on steel, as was enacted in the United States, could see suppliers mine more domestically. However, greater supply will lower the prices they can sell to a manufacturer if demand remains unchanged. Hence are they motivated to increase production at all, especially if they’re a monopoly? Let’s say not, and prices remain high.

Here, the layout of the entire industry is important. A monopoly in steel supply can set any price it wants. A steel industry in perfect competition will likely increase production and lower the selling price of steel through greater supply. To make the same amount of profit, they can sell more steel, or increase their selling price to manufacturers. But if other companies are lowering their prices, the race to the bottom commences.

In a monopoly, manufacturers have greater costs when purchasing steel. This cost can be paid by the manufacturer and reduce its gross profits, or they could charge a higher fee to a distributor to transport the goods. The distributor could then charge a store a greater fee to purchase the goods. If the retailer seeks to pass on this greater cost, it’s felt by us, the consumer. This process of passing costs down the supply chain is common across various sectors.

What’s better then? A monopoly choosing any price it wishes, or perfect competition inciting greater business activity which sees supply rise and prices fall?

The one element of this that I haven’t discussed, which breaks open this entire discussion, is demand.

After Trump’s steel tariffs were enforced in 2016, rising steel prices saw demand fall. By 2020, Great Lakes Works, one of the biggest steel plants in the United States, closed operations and saw 1250 people out of a job. Trump had promised to increase steel demand through infrastructure projects, a plan he didn’t follow through on. This is a clear example of a situation where supply and demand aren’t balanced efficiently, and we see sharp changes in price as a result.

Perfect competition, in my opinion, should be encouraged in the energy sector, because cost competition in a sector will raise energy supply and if balanced correctly by demand, should lower costs.

It needs to be encouraged to start businesses in the energy sector. I’m aware this won’t occur overnight, but extra incentives should be given to those who wish to start energy companies that will clean up our world. After all, these companies have the potential to be some of the biggest companies in the world in a matter of decades. But inefficiencies can’t be maintained. Energy production methods beneficial to our unique environments must be prioritized, and the efficiency and affordability metrics discussed in this series thus far all have a place in informing our decisions. Methods to analyse the success or failure of subsidies are needed, otherwise, we risk fuelling further inefficiencies in the West and falling behind.

Is More Better?

Finally, this idea assumes that more is considered better in this world. In this world, more is spent every day, and more is consumed every day. To keep up, the world works harder. More is produced, which requires energy. We continue to use more energy every day.

If we accept that we have enough in life where we are currently, and we don’t seek bigger houses, a bigger car, and more energy, can we more easily balance energy supply and demand?

Do tariffs undermine the efforts of countries to balance supply and demand? Are countries even trying to balance supply and demand at all? Or are they trying to increase demand, and hence generate economic growth to pay the exorbitant debts we’ve built up that are worsening from year to year? Are we boosting demand with no viable way to allow supply to keep up?

Concluding Remarks

There are examples of subsidies working effectively, and other examples where they aren’t as successful. When it comes to the energy sector, can we create an industry resembling that of perfect competition to lower costs felt by consumers at the end of the supply chain? Is this scenario not of an advantage to us at all? If you believe so, let me know in the comments. After all, this is just the ramblings of one man who had a thought in his head.

There’s still much to cover here and this piece is very big-picture level. The credit cycle sees debt costs rise and hence affects costs. How do changes in credit during periods of economic expansion or decline affect innovation? Some areas can also become subsidy-dependent. What can be the effects of this? Finally, the biggest effect of tariffs has been the trade war between the United States and China. I’ll explore this and subsidies and tariffs in greater detail next week.

Thanks for reading! I’d greatly appreciate it if you were to like or share this post with others! If you want more then subscribe on Substack for these posts directly to your email inbox. I research history, geopolitics, and financial markets to understand the world and the people around us. If any of my work helps you be more prepared and ease your mind, that’s great. If you like what you read please share with others.

Key Links

The Geopolitics Explained Podcast

If you want to see daily updates and discover other newsletters that suit you, download the Substack App.

You can become a paid subscriber to support my work. There are long-form monthly articles in my global questions series exclusively for paid subscribers. Read Geopolitics Explained for 20p per day or start a free trial below to find out if my work is for you! I appreciate your support!

Sources:

https://www.iea.org/topics/energy-subsidies

https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/climate-change/energy-subsidies

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/energy-payback-time

https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/tariffs_e/tariffs_e.htm

https://www.wto.org/english/blogs_e/data_blog_e/blog_dta_01aug24_e.htm

https://www.investopedia.com/terms/t/tariff.asp

https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/trade

https://www.sumup.com/en-gb/invoices/dictionary/tariff/#:~:text=Tariffs%20are%20paid%20by%20the,tariff%20along%20to%20the%20consumer.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0921344920302925

https://gocardless.com/guides/posts/how-to-calculate-payback-period/

https://energyeducation.ca/encyclopedia/Payback#:~:text=The%20Energy%20Payback%20Time%20or,48.83%20MWh%20to%20do%20so.

https://www.iisd.org/story/the-united-kingdom-is-to-subsidize-nuclear-power-but-at-what-cost/

https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade-and-investment-policy-watch/2021/biden-and-europe-remove-trumps-steel-and-aluminum

https://www.nbcnews.com/business/economy/trump-steel-tariffs-raised-prices-shriveled-demand-led-job-losses-n1242695